A story from Victorian London: Mary Rainbow and her nameless murdered child

Mike Pollitt | Monday 6 August, 2012 14:28

Mary Rainbow had a lovely name, but her three-week-old child had none. The baby, a girl, was illegitimate. Her father was married, but not to Mary Rainbow.

On the 12th May, 1879, labourer William Stocks left his home in Clapton and went to work just off the Seven Sisters Road.

“I was engaged in repairing a wall in the Green Lanes opposite the Manor House about 7.40 a.m.—while I was taking some bricks off the wall I saw a brown paper parcel laid up against the wall…I went down to the parcel—the paper was lying open—I looked under the paper and saw the dead body of a little child—a little flannel was wrapped over its feet.”

Mary Rainbow’s baby had been been drugged with laudanum; her skull was fractured. The child was never named. She had existed, but barely at all.

Mr and Mrs Hull, by contrast, did have names, but did not exist. In April, a couple bearing that name had come to London from Bedfordshire to have a baby. On the 22nd it had been born in a St Pancras lodging house kept by Ann Starling and her daughter Betty. A month later, the Starlings received a letter from Mrs Hull, now back in Bedfordshire.

Dear Mrs Starling,

I hope you won’t think I have forgotten you as I have not written to you, but I have been busy. I am very happy to say we arrived home without catching any more cold, and this leaves us all quite well, and hope it will find you better. My breast is nearly well…give my love to Betty, I hope she is well. I suppose she missed the baby, for I know she was very fond of nursing it. I have thought about you all a great many times since I have been away; the country seems dull after London, but still it looks very nice, everything is looking so green; I think I shall rather like it this summer.

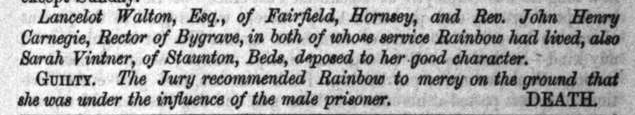

This letter, like Mrs Hull, was a lie. The baby was a week dead. Mrs Hull was Mary Rainbow, a 28-year-old servant. Mr Hull was James Dilley, 41, a married man with three legitimate children who worked as a postman and picture framer. The summer of 1879, which Mary thought she would rather like, did not turn out so well. At the beginning of August, she and Dilley stood trial for murder. By the month’s end, they were due to hang. The sentence is preserved, with brutal concision, in the Old Bailey’s record:

Despite the jury’s recommendation, there was no other sentence available to the judge in a case of murder. Who drugged and struck the child is not certainly known, but Mary claimed her innocence. The London Telegraph report from the week before the execution, preserved in the online archives of the New York Times, says:

“The prisoners still continue in a very depressed state, especially the woman Rainbow, who takes but little food. She has made a statement respecting the murder, in which she avers that she was most fond of the child, and that Dilley took the infant from her and went away with it. When he returned he said he had got rid of it. He was a married man and feared that his wife would hear of the birth of the child.”

Mary Rainbow became a cause. A petition for her reprieve was set up and presented to the Home Office. Two days before she was due to hang, Mary Rainbow was reprieved. James Dilley, the father of the child, and it all probability its killer, had no such luck. He was hanged in Newgate prison on 25th August 1879.

Child murder, specifically baby murder, was a tragically common response to the twin pressures of poverty and shame which attended illegitimate births in this period. Some 30 years before, in 1860, Henry Mayhew estimated that 225 children under two were murdered by their parents in London each year. The gruesome, murderous practice of baby farming continued even into the 20th century. Babies, especially illegitimate babies, could be both economic drains and social disasters. Death was often a rational response to their birth.

Her child dead, her lover hanged, what of Mary Rainbow’s end?

The Bedfordshire county records complete her story:

“The 1881 census shows that she was still in prison, as might be imagined, at “H.M. Fem[ale] Convict Prison, London District of Fulham”. However, by the 1891 census Mary Rainbow was out and, remarkably, back home [in Bedfordshire], working as a domestic servant at Mayfield Farm, Lower Stondon. The 1901 census shows her working for the same family, the Russells, at Chibley Farm, Shillington. Shillington parish registers show that she died at the end of 1934, aged 83 and was buried in Shillington churchyard on New Year’s Day 1935.”

Mary Rainbow had a lovely name, and an apt one too. Her life a mix of sun and rain.

Image – Rainbow at Kings Cross, taken near to the spot where Mary gave birth to her child. By Flickr user Mark Hilary, under Creative Commons license.

Links:

Old Bailey Online – August 1879 for details of the trial.

Befordshire Council – Details of the case, and biographical details of the protagonists

Henry Mayhew statistic – The London Underworld in the Victorian Period

New York Times – The Hornsey Child Murder

London Historians – Baby farming

Snipe Highlights

Some popular articles from past years

- Nice map of London's fruit trees shows you where to pick free food

- Peter Bayley has worked for 50 years as a cinema projectionist in East Finchley

- Hope and despair in Woolwich town centre

- The best church names in London, and where they come from

- Only 16 commuters touch in to Emirates Air Line, figures reveal

- Punk brewery just as sexist and homophobic as the industry they rail against

- 9 poems about London: one for each of your moods

- The five spookiest abandoned London hospitals

- The five best places in London to have an epiphany

- Number of people using Thames cable car plunges

© 2009-2024 Everywhen Ltd.