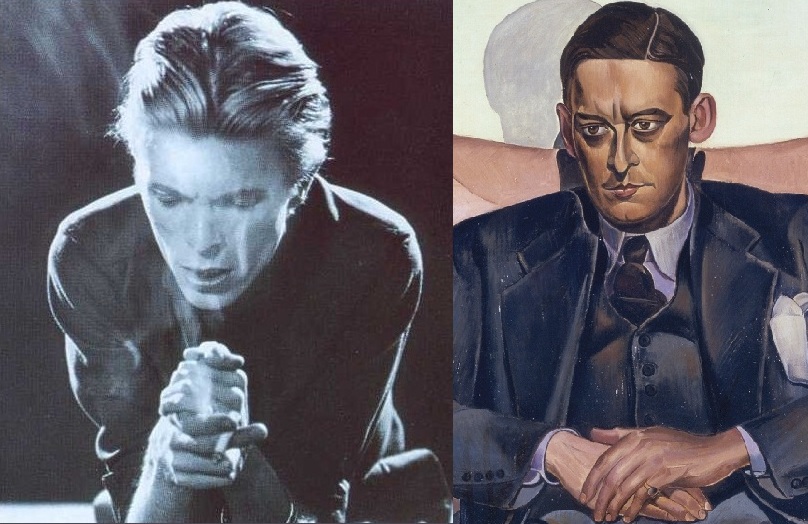

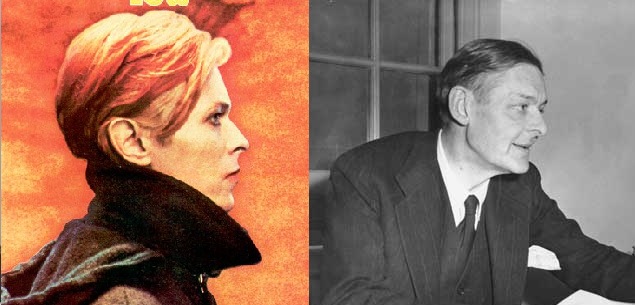

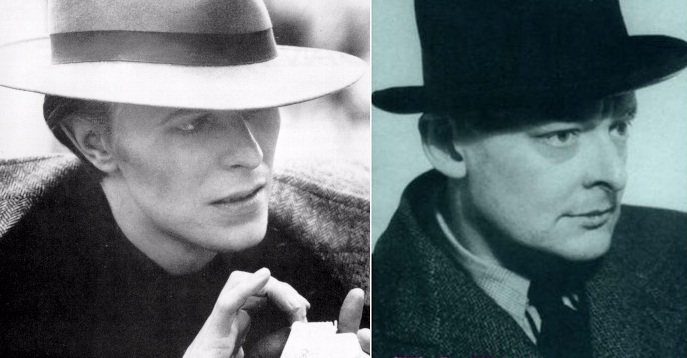

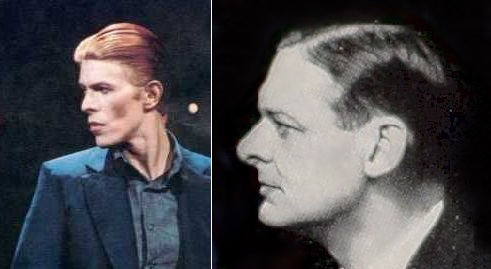

Proof, in pictures and words, that David Bowie is the TS Eliot of our time

Kathryn Bromwich | Friday 11 January, 2013 11:15

Fragmented language, Nietzschean elitism, and disillusionment with art: could Low have been inspired by The Waste Land?

Both ground-breaking in their respective fields, they antagonised readers and listeners with obscure references and unusual structures. Eliot and Bowie showed similar signs of frustration with their contemporaries, but the two have only rarely been linked to one another.

In a 1974 interview between Bowie and William S. Burroughs, himself a devotee of Eliot’s cut-up style, the following exchange took place:

Burroughs: I read this ‘Eight Line Poem’ of yours and it is very reminiscent of T.S. Eliot.

Bowie: Never read him.

Burroughs: (Laughs) It is very reminiscent of ‘The Waste Land.’

Bowie considered Burroughs to be ‘the John the Baptist of postmodernism,’ so it appears likely that he would have followed up on this. Three years later, Low was released.

Both early Eliot and Bowie’s Thin White Duke persona were interested in literature, mysticism and the occult, and both entertained a quasi-Nietzschean intellectual elitism coupled with ostensibly conservative views. Nervous and eccentric behaviour is another point in common: Eliot occasionally wore green face powder and demanded to be called ‘Captain,’ and you’ve probably heard the rumours about Bowie preserving his urine in the fridge to avoid being cloned by aliens.

The TWD’s fashion sense also seems to be modelled on Eliot’s dandyish appearance: pale, thin, with slicked-back hair, austere monochromatic clothes, a fedora hat and black overcoat.

Both works were composed in volatile political times, and Eliot’s and Bowie’s psychological conditions were far from stable. Outer and inner worlds became increasingly difficult to express through language: both felt a distrust of semiotics, lamenting the impossibility of precise utterance, so their work became increasingly non-linguistic. Eliot concentrated on the poem’s visual and spatial elements, bringing attention to the form. Similarly, Low is mainly instrumental, and the few lyrics are enigmatic. Both subverted expectations, drawing attention to the artifice, and form began to merge with content.

The artists both challenge the idea of a single, fixed identity: they hide their own personality by giving a voice to numerous different characters. The Waste Land, originally entitled ‘He Do the Police in Different Voices,’ provided an outlet to the thoughts and speech of characters within the personality of Eliot. Bowie, known for his chameleonic alter-egos Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, in the guise of the Thin White Duke splits even further: ‘Be My Wife’ is sung in a theatrical cockney accent, ‘Warszawa’ suggests someone from Eastern Europe, and ‘Breaking Glass’ is performed in a terse, unemotional voice. The juxtaposition of speakers undermines the idea of one central voice or of one correct meaning: we are never sure who the ‘real’ Bowie or Eliot is.

Perhaps counterintuitively, Eliot and Bowie both allude extensively to traditional forms of their particular art in their attempt to modernise themselves: Eliot refers to Chaucer and Baudelaire, and Bowie alludes to old-fashioned and foreign music including chanting, harmonicas, ragtime riffs and saxophones. These are then set against modern techniques: Eliot’s untraditional versification is at odds with the classical poets he references, and Bowie’s synthesiser sounds especially futuristic when contrasted to ragtime piano jingles.

Both works, bringing to light the impossibility of originality, are characterised not by an intrinsic ‘newness’, but by a Modernist yearning for the new. And this, I would argue, is what makes both works so innovative: they seem to admit that they do not operate in a cultural vacuum, and that they are not – and cannot be – original.

Still not convinced? Here are 4400 more words on the subject, with references and research and stuff, based on an essay I wrote in 2009.

Follow Kathryn on Twitter @kathryn42 and check out her blog London Scrawling.

See also:

In-depth interview: Flash fiction publisher Holly Clarke explains how a 60-word story can still mean something

Read ‘the worst poet ever’ William McGonagall’s terrible poem about London

Snipe Highlights

Some popular articles from past years

- Hope and despair in Woolwich town centre

- Peter Bayley has worked for 50 years as a cinema projectionist in East Finchley

- Silencing the Brick Lane curry touts could be fatal for the city's self-esteem

- Nice map of London's fruit trees shows you where to pick free food

- Number of people using Thames cable car plunges

- The five spookiest abandoned London hospitals

- An interview with Desiree Akhavan

- Could red kites be London's next big nature success story?

- Punk brewery just as sexist and homophobic as the industry they rail against

- London has chosen its mayor, but why can’t it choose its own media?

© 2009-2026 Snipe London.