Conflict over new Dalston flats goes beyond the usual gentrification angst

Mike Pollitt | Tuesday 17 September, 2013 10:38

How the Teardrop might look from Ridley Rd market in Dalston. Image from planning documents

Arguments over whether Hackney council should approve a proposal for a new block of flats in Dalston (or “Teardrop” of flats, to give it its marketing name) are worth following because the same arguments will be repeated across inner London over the next decade as councils attempt to reconcile some irreconcilable desires.

For the fight over the Teardrop is a minor battle in a larger war – a war about what Zone 2 of London will look like, and what it will be like to live in, in 10-20 years from now.

Here are four key arguments which will help decide that conflict.

Argument #1: “Just build it” vs “it matters who can buy”

Where national and regional politicians are attempting to intervene in London’s housing market, it is primarily with the aim of encouraging developers to build. That’s the motivation behind Mayor Boris Johnson’s new London plan, which relaxes requirements on affordable housing targets.

The government’s Help to Buy scheme is just as much a Help to Build scheme – aimed at giving developers confidence that someone will be able to afford to buy the homes they are thinking about building. The argument against these policies is that by focusing on increasing housing supply without regulating what is supplied, politicians are doing nothing to mitigate, and much to make worse, the problems of runaway prices in Inner London.

The argument in favour is that it’s better to build “unaffordable” properties than to build nothing at all. The proposed Teardrop will bring 14 “affordable” flats to Dalston. If it’s not built, will any come from another source?

Argument #2: “A ‘European’ renting model might be a good thing” vs “beware a new feudalism”

The Teardrop plans promise 14 “affordable” flats from a total of 125 (11%). So the buyers envisaged for the remaining 111 properties will be paying an “unaffordable” amount to own them. In other words, they are investments first, and homes second. This is not a surprising, because over the last 20 years it has become the established reality in inner-London.

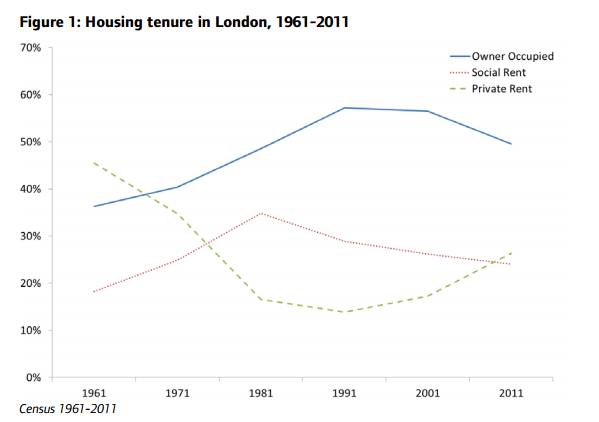

Across the city as a whole, the proportion of people who own their own homes is at its lowest level since 1981. There’s an argument that in a city with a fast growing population, which attracts high numbers of domestic and international migrants (c. 200,000 domestic and 150,000 international per year), it makes sense to move away from an owner-occupier aspirational model. Long term renting is already reality for a lot of people. Perhaps it’s time to accept that fact and make the best of it with new rent regulations and a shift in expectations.

The counter argument – that this model would be a recipe for entrenching land wealth across generations – is nailed by Faisal Islam in a passage from his book The Default Line, extracted in the Guardian:

“The property ladder was a one-off opportunity for a lucky generation-and-a-half. Now we are back to a kind of neo-feudalism, in which your quality of life depends on who your parents are, and what they owned.”

For inner-London at least, this future seems already here.

Argument #3: “Conservation is vital” vs “NIMBYs in the path of progress”

There’s an unpopular case to be made that a fast growing city needs to be less fussy about appearances and more attentive to the needs of its new inhabitants. In the case of the Teardrop, should a new block of flats be opposed in part because it overshadows a grade II listed Edwardian eel shop?

And to travel south down Kingsland Rd, to the shell of the Marquis of Lansdowne, should a pub building that has not been a working pub for 20 years be preserved so it can remain not-a-pub for 20 years more?

The instinctive reaction of many Londoners is often to preserve their heritage. But preservation, especially of unused things, has its own costs.

Argument #4: “Social cleansing” vs “regeneration”

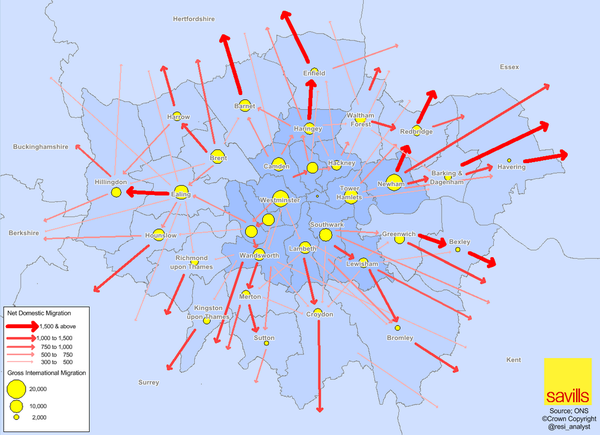

Map of London’s population flow, for Savills, by @resi_analyst. Domestic migration is shown by red arrows, international immigration by yellow blobs.

The Teardrop is a symbol of advanced gentrification. A tall building to house affluent renters could only be proposed in an area where those renters want to live. Dalston’s great transformation has already happened. This development – or if it’s rejected, another quite like it – will just confirm that fact in glass and steel.

But the great fear accompanying gentrification/regeneration, and the rising land values that come with it, is that existing, rooted populations will be pushed out by rootless newcomers. Academic careers have been spent assessing the extent to which this analysis holds, and what measurable damage to “the sense of community” ensues. Can you stop this process by stopping the Teardrop? Can you control the process by pushing for more affordable homes, more social housing? If you try to do stop or control it, will you get the new homes that you need? These are questions that don’t answer as easily as some might like.

The Teardrop is a symbol of all these arguments. But exactly what the symbol means is still up for grabs.

Snipe Highlights

Some popular articles from past years

- Nice Interactive timeline lets you follow Londoners' historic fight against racism

- A unique collection of photos of Edwardian Londoners

- Could red kites be London's next big nature success story?

- Random Interview: Eileen Conn, co-ordinator of Peckham Vision

- The five spookiest abandoned London hospitals

- Only 16 commuters touch in to Emirates Air Line, figures reveal

- Hope and despair in Woolwich town centre

- Silencing the Brick Lane curry touts could be fatal for the city's self-esteem

- 9 poems about London: one for each of your moods

- The five best places in London to have an epiphany

© 2009-2026 Snipe London.