Let's look at some young artists from Russia: Calvert 22 “Practice for Everyday Life”

Leah Cowan | Tuesday 12 April, 2011 14:08

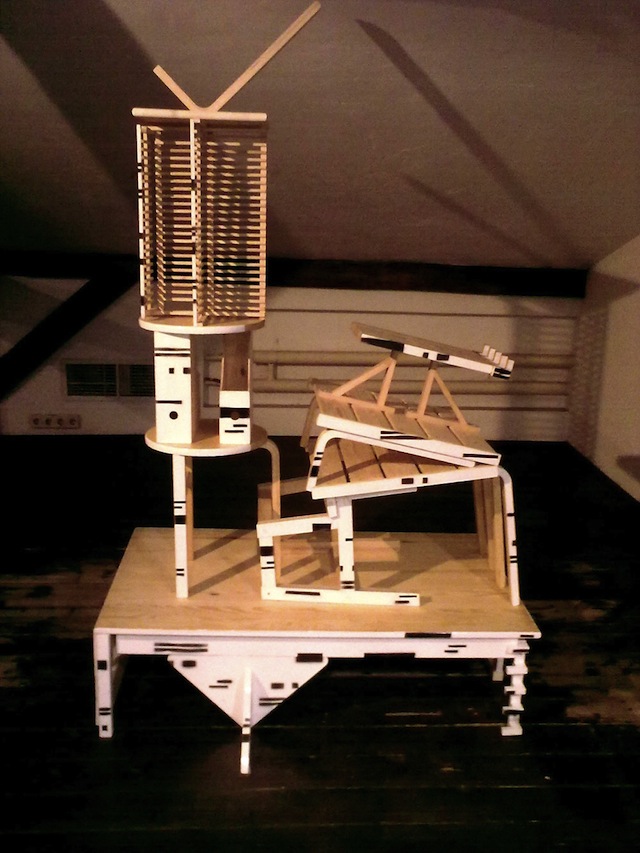

Olga-Bozhko – “Tree-(Tree-Wood)” 2010, Courtesy the artist and Calvert 22.

Until 29th May 2011

Wednesday-Sunday: 12pm – 6pm

The new exhibition of Young Artists From Russia- “Practice for Everyday Life”- at East London gallery Calvert 22, takes its title from the book of the same name written by Michel de Certeau in 1980. De Certeau’s book explores the way in which people individualise mass culture, and critiques the presentations of individuals as passive receivers of culture and ‘non-artists’.

The artists in the exhibition have created works which, unlike their predecessors’, are able to respond free and unfettered to environments and ideas on the contemporary art scene, without fear of reprimand or consequence as experienced in the 1920s by the Russian Avant-Garde, and to a lesser extent, in the 1970s by the Moscow Conceptualists, as socialist rule began to slacken its steely grip. In some manner, the artists explore their individualities through pieces which constantly return to ideas of identity, locality, spatiality, autonomy and community. Yet, it is interesting to weigh up how far the artists challenge the dominant ‘status quo’ in their works, or conversely, to what extent their pieces perpetuate universalised ideas about ‘mass’ culture through presenting artworks which do not critique normative ideas about the form and content of ‘art’.

It is notable that the pieces in the exhibition feel at times disparate, floating, and lacking in directedness. Perhaps due to the constraints of the small gallery space, pieces are placed together in an almost arbitrary way which sometimes fails to complement the art work. Arseniy Zhilyaev’s mock-up lounge installation- Words- featuring an armchair and a coffee table on a large Persian rug, strives to subtly colour the boundary between the personal and intimate; public and communal, but is tainted by its position next to a large floor-to-ceiling window, bringing passing cars and pedestrians directly into the gallery space, and leaving Zhilyaev’s piece less Ilya Kabakov, and more DFS showroom.

Equally, the remarkable majesty of Sergey Ogurtsov’s delicate origami-esque structures, constructed from bent, looped and folded book pages, are somewhat overwhelmed by the oppressive, low-ceilinged underground room in which they are exhibited. Ogurtsov’s manipulated books look like tiny temples; indeed he talks about his objects as the very, “hybrid of sacred and everyday”. Ogurtsov examines the fetishisation of objects; objects which he elucidates as essentially meaningless, stating that, “Artform is both a condition of and possibility of a message with a ‘zero degree’ of meaning”. The artists’ work explores oft-contradictory nuances between the ‘mass cultural’ fetishisation of production-line created objects which are inherently void of connotative meaning, but are however, in their daily usage clouded with heavy social, ceremonial and ritual aspect.

Olga Bozhko’s sculpture; a structure made of wooden, Ikea-esque flatpack household items- Tree- we are told, satirically unpicks the relationship between the raw materials of nature, and their usage in a consumerist society predicated upon cookie-cutter Fordist production methods, which we sense that Bozhko is suggesting, bastardises their organic origins. These pop-together items; CD racks, paper tidies and kitchen stools are wholly unremarkable in their design, but gather meaning through their daily usage. Simultaneously the artists reacts against conventional modes of piecing these items together; the slatted back of a chair is erroneously affixed to the top of a table, and the piece metamorphoses from a collection of flat wooden pieces, into an amorphous leviathan of distorted and amputated consumerist items.

Curator Joseph Backstein describes the exhibition’s self-confessed endeavour to insert itself into an international discourse of art, in ways which at times almost pointedly neglects to observe itself either within, or without of, the arena of Russian art history. In contradiction to this, co-curator David Thorp discusses the artists’ exploration of their ‘social and cultural identity’, a sentiment which seems at odds with the desperation to shoehorn the work of these artists into an inevitably mainstreamed ‘global art-scene’.The beautiful film created by Taus Makhacheva- Rehlen- locates itself far from global mainstream culture, whatever that may be, and deep in the foothills of rural Dagestan. Makhacheva films her husband integrating himself into a flock of sheep, by donning the traditional sheepskin coat worn in the past by shepherds. The artist explains that her work explores ideas of belonging, identity, and ‘the other’, and challenges the viewer to question what they would be prepared to do in order to realign themselves with a tradition and community; would they humble themselves on all fours? Amusingly, a boorish critic at the press view of the exhibition approached Makhacheva and asked her in the booming public school timbre of one who likes to be acknowledged, to ‘get him one of those sheepskin coats’ next time she goes to Dagestan. When Makhacheva pointed out that the coat has no functional use in non-shepherding contexts, as the sleeves are traditionally sewn up like long conical mittens, the critic absent-mindedly picked an imaginary thread off his camel coat and suggested “well I could just cut them open, couldn’t I?”. A bemused Makhacheva took the request in good humour, but the critic unknowingly, poignantly revealed the crux to the artist’s work, and perhaps the way in which, for some of these artists, arbitrary stabs at aligning themselves with half-hearted manipulations of ‘Western’ contemporary art detracts from the specificity of their context. Makhacheva’s work is not predicated upon gimmicky pop art-tactics or sideswipes at consumerism, but sensitively examines the intersection between personal and geographical identity. In contrast, the art critic seemed to mark his own value and identity in purchasing power, and his ability to import exotic relics to be transformed into symbolic capital and slung over his Art Deco club chair.

It is not unfair to say that, thus manipulated by the curators into a context of ‘discussions on the global contemporary art scene’, some of the works in “Practice for Everyday Life” fall flat. Yulia Ivashkina’s flailing attempts at Surrealism are anchored by resonating theoretical underpinnings, and she describes almost a différance of image, in which images denote meaning not innately, but through their positing in relation to other, ungrounded images. Unfortunately, claims that her paintings create “imaginary spaces constructed of real objects” are laughable; there is limited artistry and technical skill in her works unlike the Surreal landscapes of Dali and Magritte, which, joyously absurd in their composition, also demonstrate great talent for mimesis. Ivashkina’s paintings lack much synthesis of either concept or craftsmanship; the failure to provide a comfortable place for the eye to rest perhaps the result of the artists’ self-proclaimed ‘montage-esque’ composition.

Equally, Anya Titova’s minimalist structure- House of Culture- similar to Bozhko’s piece, in that it is in essence a shelving unit, is so painfully self-aware in its ideology that it fails to really bring anything useful or even comprehensible to the table. Titova refers to her work as a “mental environment of architectural suspense”; a phrase so contorted and bound up in itself that it manages to say precisely nothing. Titova’s work is almost a damning parody of the artworld of the artphobe- the statement that “her works are linked to the disappearance of everyday aesthetics in design” is invalidated surely, by the commonly assumed premise that everyday aesthetics is design?

Evident, rightfully or not, is a distinct distance between the artists who, as self-titled ‘Young Russian Artists’, draw on the artistic canon of Russia, such as Alexander Ditmarov in his short video- Play With Me- and those who eschew any allegiance to it, and grasp at ‘Western’ Minimalism, Surrealism, Conceptualism, and Pop Art in ways which miss the point, or are at least two steps behind it and end up misrepresenting their artistry. Ditmarov’s piece, a close-up video sequence of an unnamed person playing a game of pool with large marble balls, reveals cadences of the bold geometric shapes of Suprematism: a vital movement in the history of Russian art. The large balls shoot across the table propelled by the loud cracking shots of the omniscient player; the motion of the shapes; grand like planets; hint to Malevichian intrigue in non-Euclidian geometry, and the manner in which shapes move through space and time.

The contrivance that to exhibit as ‘young’ artists in a hip East London gallery you must forgo the texture of your own identity and artistic sensibility has perhaps clouded judgement in the exhibition. It could be surmised therefore, that the exhibitors whose works pivot upon senses of intimacy, immediacy, and emotivity, far outstrip the pieces created by the artists who attempt to divorce themselves, and their human-ness from their own landscapes. Curator Backstein laments the lack of a Russian ‘lineage’ of art, but at the same time condemns Russian artists to appropriating the aesthetics of Warhol in order to possibly be modern.

In a historical moment where standardising dominant discourses attempt to normalise the retraction of arts funding and thus threaten to deaden the artistic vibrancy of a generation, it is ever more pertinent to create art which strikes out against political action which runs counter to the will of the people. Attempts at ‘YBA’-esque likenesses are pointless and transparent in their superficiality, and the presentation of an exhibition of pointedly ‘Young Artists From Russia’, which is not in dialogue- whether that be harmonious or conflictual- with its innate Russian-ness, should not therefore be entitled so.

Snipe Highlights

Some popular articles from past years

- The best church names in London, and where they come from

- A unique collection of photos of Edwardian Londoners

- Margaret Thatcher statue rejected by public

- The five best places in London to have an epiphany

- Could red kites be London's next big nature success story?

- Punk brewery just as sexist and homophobic as the industry they rail against

- Number of people using Thames cable car plunges

- Nice map of London's fruit trees shows you where to pick free food

- The five spookiest abandoned London hospitals

- Summer Camp: Roll out those lazy, hazy, crazy days

© 2009-2026 Snipe London.