Blasted, A Moment of Silence

Alan Hindle | Tuesday 2 November, 2010 18:50

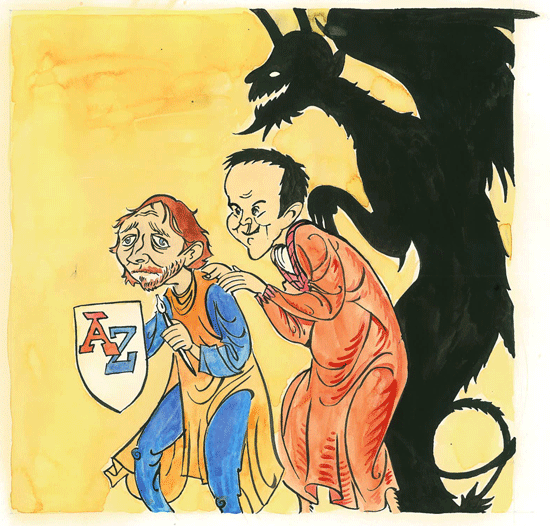

Alan Hindle illustration

THE HOLY GRAIL is the holy grail of knights on a grail quest. The rest of us are just trying to get by. To those living in a world of perpetual gloom and despair the dream is often just to see tomorrow.

For some, it’s to not have to see another tomorrow, an altogether darker quest, yet whether it’s because there is no such thing as tomorrow, or due to fear, or to a very subtle kind of courage, the sun usually rises again. A kernel of optimism, of fantasy, a skewed logic involving statistics and karma keeps everybody going. We’re all on a grail quest. It’s just a matter of personal scale.

In A Moment of Silence, Amos sleeps on a park bench with nothing but a threadbare blanket for warmth. Every morning his only friend, Lou, appears and they resume Amos’s search of the city with the aid of his A-Z and a precious unused pen that isn’t his. What they’re looking for is never stated but the urgency of nearly a decade’s searching has left Amos a fractured, downwardly spiraling nut. Even when he speaks, it’s in circles. Maybe he doesn’t need the atlas, he just orbits the park.

Repeating sentences, revolving around words and the words within words that produce opposing meanings, there is a kind of medical poetry to Amos’s madness that is, at times, hugely irritating. The deliberately lyrical, “Beckettesque” writing, and the elementary psychology used in Silence got on my nerves for the first fifteen minutes. Then it began to work, as a medieval quest tale, as a circle poem. I began to see Amos more as a hero who’s done something unforgivable for which he must forgive himself. Lou, and other characters I’ll call The White Hoodie, and Castle Girl With Soup pop in and out of Amos’s reality, playing the same roles that guides and devils play in all medieval myths. They waiver between two and three dimensions, as fairy tale folks should, but with steady layering Amos becomes a real person.

THE BRUTALITY OF LIFE is something that completely escapes the “modern” world. Until madness smashes some poorer corner of it. A few sanitised details make their way into the papers, but most of us pass over the awful headlines to be shocked instead by some football player’s infidelities, or even a child’s brutal murder described with button-pushing euphemisms. These crimes, the most we seem able to handle over breakfast, are in scrubbed and sanitised language, and we are appalled for fifteen minutes until we come to the sport section and are happy to find the unfaithful sport hero will still be on the team next week.

In Sarah Kane’s mesmerising Blasted, the logic of man’s illogical, poisonous nature is followed ruthlessly to its bitter end. Ian, a tabloid, or perhaps war/crime journalist has taken his former girlfriend, Cate, to stay at a hotel. They’ve known each other for years, so it’s obvious he was sleeping with her when she was underage. Appalling! He is a racist, homophobic, asshole, and takes advantage of her medical condition of periodically fainting to rape her fully clothed. Repulsive! Even more disgusting, though there are emotional vagaries in their relationship that make it difficult to pass easy judgment.

Then a soldier bursts in, steals Ian’s breakfast at gunpoint, a bombs lands, and this theatrical world falls apart. Up until now the naturalistic setting and structure has lulled us into believing what we were seeing was an evil man doing evil things- and he was- but now we suddenly find ourselves in a war, and a new context makes plain we knew nothing about right and wrong. As the play becomes more fractured and expressionistic it also becomes more real.

Rape, murder, devouring children, sucking a man’s eye’s out, nightmares we can barely read even in a theatre review without feeling squeamish, escalate in cruelty and unfathomable pain. Someone seeing Blasted might find it disgusting and barbaric, but around the world and thoughout history, in Africa, Eastern Europe, Asia, the Americas this was/can be normal life. The notion that such insanity could never happen here is delusional. Being good is work. Ethical laziness is a shortcut to the dark side, and claiming ignorance, or distaste, or righteous indignation for the unsavoury facts of human nature is the first step on that brief path to a new normality.

A brilliant show with three powerful performances. I’ll tell you what, for unsettling, disturbing, brain-rejigging horror, Blasted kicks the shit out of Ghost Story.

Snipe Highlights

Some popular articles from past years

- The best church names in London, and where they come from

- Nice map of London's fruit trees shows you where to pick free food

- The five spookiest abandoned London hospitals

- A unique collection of photos of Edwardian Londoners

- Margaret Thatcher statue rejected by public

- Hope and despair in Woolwich town centre

- Punk brewery just as sexist and homophobic as the industry they rail against

- Random Interview: Eileen Conn, co-ordinator of Peckham Vision

- Only 16 commuters touch in to Emirates Air Line, figures reveal

- Silencing the Brick Lane curry touts could be fatal for the city's self-esteem

© 2009-2026 Snipe London.