Practice for Everyday Life

Lauren Down | Friday 13 May, 2011 18:27

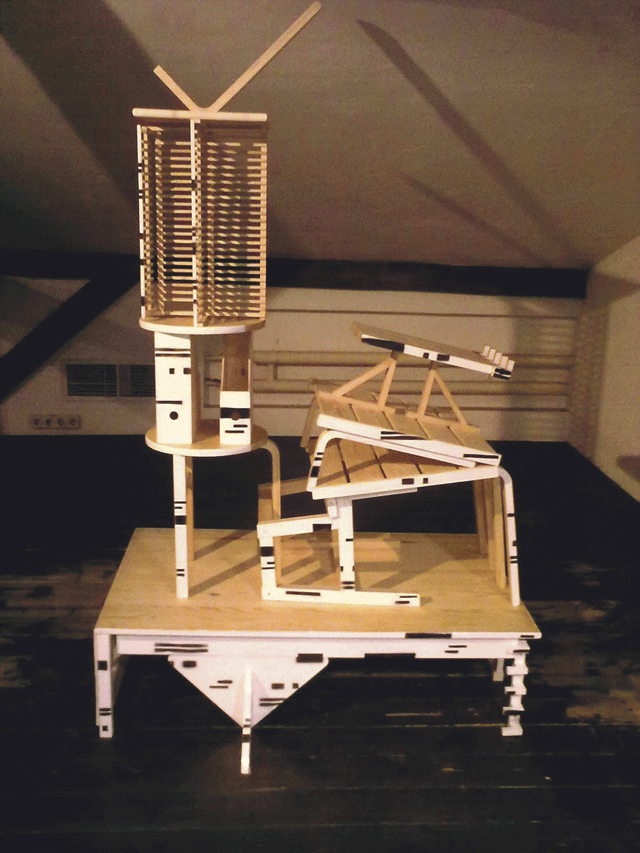

Olga Bozhko ’Tree-(Tree-Wood)’, 2010 Courtesy of the artist and Calvert

The young Russian artists exhibiting at Calvert22 have created works which, unlike their predecessors’, are able to respond free and unfettered to ideas on the contemporary art scene, without fear of reprimand or consequence. It is interesting to assess how far the artists challenge the dominant ‘status quo’ in their works, or conversely, whether their pieces perpetuate universalised ideas about ‘mass’ culture through presenting artworks, which fail to critique normative ideas about the form and content of ‘art’.

It is notable that – perhaps due to the constraints of the small gallery space—the pieces in the exhibition feel at times disparate, floating, and lacking in directedness. Arseniy Zhilyaev’s mock-up lounge installation Words featuring an armchair and a coffee table on a large Persian rug, strives to subtly colour the boundary between the personal and public, but is tainted by its position next to a large floor-to-ceiling window. Passing cars and pedestrians are transported directly into the gallery space, leaving Zhilyaev’s piece less Ilya Kabakov, and more DFS showroom.

Equally, the remarkable majesty of Sergey Ogurtsov’s delicate origami-esque structures, constructed from bent, looped and folded book pages, are somewhat overwhelmed by the low-ceilinged underground room in which they are exhibited. Ogurtsov examines the fetishisation of objects; objects which he elucidates as essentially meaningless, stating that, “Artform is both a condition of and possibility of a message with a ‘zero degree’ of meaning”.

Olga Bozhko’s sculpture Tree—a structure made of wooden, Ikea-esque flatpack household items we are told—satirically unpicks the relationship between the raw materials of nature, and their usage in a consumerist society predicated upon cookie-cutter Fordist production methods, which we sense that Bozhko is suggesting, bastardises their organic origins.

The beautiful film created by Taus Makhacheva entitled Rehlen locates itself far from global mainstream culture, whatever that may be, and deep in the foothills of rural Dagestan. The artist explains that her work explores ideas of belonging, identity, and ‘the other’. Makhacheva’s work is not predicated upon gimmicky pop art-tactics or sideswipes at consumerism, but sensitively examines the intersection between personal and geographical identity.

Alexander Ditmarov’s piece, a close-up video sequence of a person playing a game of pool with large marble balls, reveals cadences of the bold geometric shapes of Suprematism: a vital movement in the history of Russian art. The motion of the shapes; grand like planets, hint to Malevichian intrigue in non-Euclidian geometry, and the manner in which shapes move through space and time.

The contrivance that to exhibit as ‘young’ artists in a hip East London gallery one must forgo the texture of their own identity and artistic sensibility has perhaps clouded judgement in the exhibition. Most of the exhibitors described above, whose works pivot upon senses of intimacy, immediacy, and emotion, far outstrip the pieces created by the artists who attempt to divorce themselves, and their human-ness from their own landscapes. Curator Backstein laments the lack of a Russian ‘lineage’ of art, but stabs at ‘YBA’-esque likenesses are pointless and transparent in their superficiality. The presentation of an exhibition of pointedly Young Artists From Russia, which is not in dialogue, (whether that be harmonious or discordant), with its innate Russian-ness, should not therefore be entitled so. Until 29 May.

Snipe Highlights

Some popular articles from past years

- The five spookiest abandoned London hospitals

- Number of people using Thames cable car plunges

- London has chosen its mayor, but why can’t it choose its own media?

- Only 16 commuters touch in to Emirates Air Line, figures reveal

- A unique collection of photos of Edwardian Londoners

- Diary of the shy Londoner

- Nice Interactive timeline lets you follow Londoners' historic fight against racism

- Random Interview: Eileen Conn, co-ordinator of Peckham Vision

- Nice map of London's fruit trees shows you where to pick free food

- Silencing the Brick Lane curry touts could be fatal for the city's self-esteem

© 2009-2026 Snipe London.